- Gateway Welcome

- Introduction

- About Me

- Major Interests

-

Publications

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War

-

War, Sex and Human Destiny

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 Background

- C2 Our Dilemma, Our Challenge War Defined

- C3 War - Nature or Nurture?

- C4 Sexual Dimorphism

- C5 Humans & Sexual Dimorphism

- C6 Equality for Women & Progress

- C7 Sex, Individuality, Leadership

- C8 Summary Conclusion

- C9 D. Fry - Life W/O War

- C10 AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C11 Global Peace System Accomplishments

- Acknowledgments

-

A Future Without War

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 - Introduction

- C 2 - The Single Most Important Idea

- C3 - How Far We've Already Come

- C 4 - Embrace The Goal

- C 5 - Empower Women

- C 6 - Enlist Young Men

- C7 - Ensure Essential Resources

- C8 - Foster Connectedness

- C9 - Promote Nonviolent Conflct Resolution

- C 10 - Provide Security & Order

- C 11 - Shift Our Economies

- C 12 - Spread Liberal Democracy

- C 13 - Differences Between Men & Woman About Aggression

- C14 - Women, Pivotal Catalyst for Positive Change

- C 15 - How Long It Would Take to Abolish War

- C 16 - Summary of AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C 17 - What Makes People Happy

- Acknowledgments

- Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace

- Fiction >

- Articles, Essays

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Contact

We now consider how sexual dimorphism in some human personality traits affects social interactions of many kinds involved in shaping a better human destiny, not just ending war. To do so we dig still deeper into biology because humans have hundreds of personality traits, and many, arguably most, traits of the sexes actually overlap. (Schmitt et al. 2008), Schwartz & Rubel 2005)

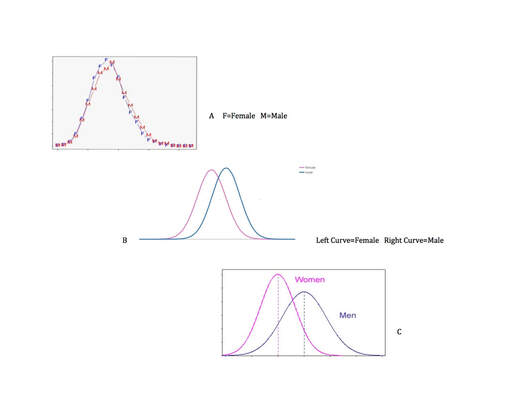

Some, however, overlap more than others. And what’s relevant to group social affairs and the shaping of our future is when differences between the sexes in expressed behavioral proclivities would make a group of men choose differently from a group of women, and a mixed-sex group choose differently from only men or only women. These graphs roughly illustrate how overlap works. Imagine that we measure three different personality traits, A, B, and C.

The range of possibilities for a given trait is plotted on the horizontal axis (like the degree of empathy for other people, ranging from virtually none to acutely empathetic, or personality type ranging from extremely shy to outrageously extrovert). The numbers of persons having a given trait is plotted on the vertical axis in a group having equal numbers of men and women. In each graph, one curve represents measurements of all women, the other represents measurements of all men.

When trait A is measured, an almost perfect overlap exists between the numbers of men and women, with most people measuring somewhere in the middle range. In a given context, with respect to trait A, the majority of both sexes would respond or behave similarly. When trait B is measured, there is some behavioral overlap in the middle of the range, but the majority of men and women behave or choose somewhat differently: male and female peak numbers of individuals are not the same. When trait C is measured, we again see some overlap, but the range of variation isn’t the same for men and women, the men’s range, on the right, being much broader. The women, in general, would be more in agreement with each other than would the men, in general. And note that the vast majority of women would not agree with the majority of men.

Figure 1 - Graphing Male and Female Personality Traits

If we could measure all human traits and plot them similarly, which in reality we can’t, but if we could, there would be many different graphs for different traits, and for some traits, different graphs in different cultures.

When considering how sexual dimorphism affects social behavior at the group level, we’re not concerned with individuals. We want to know whether statistically significant differences between the proclivities of the sexes will cause groups to behave differently. This relates directly to the outcomes of all-male governing (patriarchy) vs. its diametric opposite, fully mature liberal democracy of the kind described by the noted journalist and author Fareed Zakaria. (Zakaria 1997) More on the current battle between the world's patriarchies and fully mature liberal democray is the subject of another essay, "Summary and Conclusion").

Nature vs. Nurture

What about the nature vs. nurture issue: the role of learning and culture? Isn’t learning what teaches us how to behave, not our genetic inheritance?

Imagine two extremely different socialization contexts. What behavior is likely to be learned and expressed by boys and girls raised in a Quaker community compared to the likely behavior learned and expressed by boys and girls raised in the Islamic caliphate of ISIS?

At one time it was thought that nurture always trumps nature, that learning and culture always trumps genetics. Much research, however, has put that idea to rest, at least for biologists. The most powerful studies on the relative influences of nature and nurture have been done using fraternal and identical twins. A recent meta-analysis by seven authors on fifty years of twin studies on over 17,000 traits conveyed an important take-away message: not even one trait was solely the result of either genetics or environmental experience. (Polderman et al. 2015) This relationship is complex; nurture is sometimes the dominant influence, but sometimes nature is. In reality, both provide significant influence on how people behave. (Sapolsky 2017)

Psychological tendencies to avoid physical violence, or improve one’s dominance status using physical violence, or an abiding concern for children and community are going to have complex environmental and genetic components—learned and inherited influences. Comparative, cross-cultural studies indicate, however, that whatever the learning environment, e.g. Quaker or ISIS, the genetic predisposition and observable adult behavior of the two sexes, certainly when considered as groups, are not identical for observed behavior involving use of physical violence, concern for children and a socially stable community, and a number of other significant behaviors as well. (Butovskaya et al. 2015, Schmitt et al. 2008, Schwartz & Rubel 2005)

Note that however influential genetics is to the behavioral choices of men and women—and it unquestionably is--individual behavior is highly adaptable and shaped by culture. (Sapolsk 2017) Individual behavior can change, people can learn to make new choices, and cultures can and do shift. Learning is what makes us so adaptable. This is a source of hope. What we see and experience now is not what inevitably must be.

Decision-making in Gender-balanced Groups

To illustrate how differences in male/female preferences play out when a gender-balanced group makes a socially critical decision, consider a simple example using war. Imagine a legislative body of twenty individuals, with equal numbers of men and women (koinoniarchy). They’ve been debating whether to go to war now—or—to let reflection and negotiation in Geneva play out longer. Emotions are running very high. In such a group, a not uncharacteristic vote of the men in a dominator society could be 7 in favor of declaring war—“we need to go kick ass”—and only 3 favoring more negotiation and reflection.

Clearly, not all men would favor war now. Some—maybe “cooler heads”—might opt for more careful reflection. If we compare that to a corresponding, hypothetical women’s vote in this culture, however, that would more likely be 2 of the women voting for war now, but 8 favoring extending reflection and negotiation a bit longer. It’s not that all the women would vote against charging into war, just that characteristically a greater percentage of them would favor more time for trying to find other options. In this not atypical gender-balanced group in a warring culture, the overall result is 9 votes for war now, but 11 for negotiating some more. This illustrates how giving women’s psychological preferences a voice in a gender-balanced group can effect a restraining or moderating influence on some characteristically male inclinations.

It’s critical to note, however, that this effect on more aggressive male inclinations won’t happen if only a token number of women are included. The exact percentage of women needed to influence a decision outcome in any social group undoubtedly differs by context and the question under consideration. For many situations the concepts of “critical mass” and “tipping point” have been offered to suggest a value around 30%, but the social chemistry of a group can sometimes be affected by even smaller female input. (Childs & Krook 2006, Dahlerup 1988)) The point being that, as history shows, the presence of only a few token women in any deciding body will not provide an effective counter to any male inclinations that differ from those of women.

Here is a real-life example of what happens when more women are included in leadership positions. In a paper looking at over 100 countries, the authors had noted that numerous previous behavioral studies found that women were more trust-worthy and public-spirited than men, are more likely to exhibit “helping” behavior, take stronger stances on ethical behavior, and behave more generously when faced with economic issues. This suggested to them that women would be less likely to sacrifice the common good for personal (material) gain. Looking deeper, they compared rates of government corruption to the percent representation of women in parliaments. It turned out that the greater the representation of women, they found the levels of corruption lower. (Dollar et al. 1999)

The Outcome of All-male Governing

In many decision-making contexts, the results achieved when women’s voices are included strongly suggests that having only one sex making all public choices all the time, e.g., all-male governing (patriarchy), might not always produce the very best result for communities over the long term (years, decades, hundreds of years, to say nothing of millennia).

Arguably that also includes the hypothetical condition of all-female governing (matriarchy). Due in part to women’s deep preference for social stability, often reflected in a tendency toward social conservatism, I speculated briefly that a society governed solely by women (we’ve never had one) would have its own pitfalls, one of the potential ones over long periods of time being a kind of social stagnation. (Hand 2003, p. 151)

As is true of so many things in life, both personal and social, the best results tend to emerge by finding balance. In the case of governing, I maintain that over time the balance of shared male/female governing is likely to produce the best results for our species. At least, would it not be worth a try?

Recorded history indicates that in the world’s dominant cultures, major social decisions involving governance have overwhelmingly been shaped by men for at least 2-3 thousands years. We know exactly how the world would work under patriarchies. We have done wonderful things. We’ve created technological masterpieces and works of stunning beauty, and explored insights into philosophy and religion. We’ve split atoms and discovered thousands of other worlds. We are indeed clever, surely a species worth saving, and for which we should build the best, most excellently nurturing future we can.

Also true, however, is that male psychological inclinations, manipulated by warmongers, have given us seemingly endless cycles of war and destruction. There is no reason to believe if we continue to operate under the same reality of male-dominated leadership that these repeated cycles of war and devastation would cease. Realistically, we may finally engage in a civilization-destroying one with weapons of mass destruction.

There is, however, strong reason for hope. Most men abhor war: actually killing other people. They can love playing at war as children, and war games as teens, even joining together to plan a war when they are adults. Men are good at and enjoy working in groups to achieve a goal, especially “winning.” (Wrangham & Benenson 2017) But normal men do not enjoy killing other people. They must be trained and conditioned to kill another human, the task of military indoctrination and conditioning. Actual participation in killing often has seriously damaging psychological effects. (Grossman 1995) That natural revulsion is a noteworthy, positive reality of what kind of animal we are.

Even what we call alpha males—a Dwight D. Eisenhower, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Nelson Mandela, Barack Hussein Obama—alpha males may find themselves involved in a war or even forced to take on an enemy that has attacked their community. But characteristically they don’t start wars.

Men who can be called hyper-alpha males, however, are different: the Genghis Khans, Napoleons, and Hitlers. Whatever good or bad they may leave in their wake, they are out of control men, virtually unconstrained by their culture, their women, or their own personal preferences. They’re emotionally driven to dominate all others, whether in a small tribal world or a world that spans continents, and are distinguished by being willing to kill or have others kill for them. They are the generators of war, the initiators of war, the warmongers.

They don’t wear a label that says “warmonger,” but they assemble an army and/or trigger theirs to strike the first blow. Contemporary versions of hyper-alpha men exist on all sides of our current conflicts. The many proximal reasons for why people make war—what they are fighting about (e.g., land, oil, religion)—have been discussed and written about in many books. I summarized the main reasons elsewhere. (Hand 2014, 31-34) In essence, war is the result of otherwise non-warring or even laudable male inclinations, described above, being malignantly manipulated by warmongering leaders in dominator cultures.

The percentage of hyper-alpha males in our populations is arguably very small. Perhaps ten percent, or even less. Warmongers are a tiny tail wagging the dog of civilization. To build that “better” future, the global community must at some point learn to identify contemporary warmongers and refuse to elevate them to positions of power, or when necessary, promptly remove them. They do harm by squandering resources needed to fully develop the cornerstones of a "better future." But even more urgently, they need to be removed before they light the fires to ignite a massive, global, and potentially existential Armageddon.

Some, however, overlap more than others. And what’s relevant to group social affairs and the shaping of our future is when differences between the sexes in expressed behavioral proclivities would make a group of men choose differently from a group of women, and a mixed-sex group choose differently from only men or only women. These graphs roughly illustrate how overlap works. Imagine that we measure three different personality traits, A, B, and C.

The range of possibilities for a given trait is plotted on the horizontal axis (like the degree of empathy for other people, ranging from virtually none to acutely empathetic, or personality type ranging from extremely shy to outrageously extrovert). The numbers of persons having a given trait is plotted on the vertical axis in a group having equal numbers of men and women. In each graph, one curve represents measurements of all women, the other represents measurements of all men.

When trait A is measured, an almost perfect overlap exists between the numbers of men and women, with most people measuring somewhere in the middle range. In a given context, with respect to trait A, the majority of both sexes would respond or behave similarly. When trait B is measured, there is some behavioral overlap in the middle of the range, but the majority of men and women behave or choose somewhat differently: male and female peak numbers of individuals are not the same. When trait C is measured, we again see some overlap, but the range of variation isn’t the same for men and women, the men’s range, on the right, being much broader. The women, in general, would be more in agreement with each other than would the men, in general. And note that the vast majority of women would not agree with the majority of men.

Figure 1 - Graphing Male and Female Personality Traits

If we could measure all human traits and plot them similarly, which in reality we can’t, but if we could, there would be many different graphs for different traits, and for some traits, different graphs in different cultures.

When considering how sexual dimorphism affects social behavior at the group level, we’re not concerned with individuals. We want to know whether statistically significant differences between the proclivities of the sexes will cause groups to behave differently. This relates directly to the outcomes of all-male governing (patriarchy) vs. its diametric opposite, fully mature liberal democracy of the kind described by the noted journalist and author Fareed Zakaria. (Zakaria 1997) More on the current battle between the world's patriarchies and fully mature liberal democray is the subject of another essay, "Summary and Conclusion").

Nature vs. Nurture

What about the nature vs. nurture issue: the role of learning and culture? Isn’t learning what teaches us how to behave, not our genetic inheritance?

Imagine two extremely different socialization contexts. What behavior is likely to be learned and expressed by boys and girls raised in a Quaker community compared to the likely behavior learned and expressed by boys and girls raised in the Islamic caliphate of ISIS?

At one time it was thought that nurture always trumps nature, that learning and culture always trumps genetics. Much research, however, has put that idea to rest, at least for biologists. The most powerful studies on the relative influences of nature and nurture have been done using fraternal and identical twins. A recent meta-analysis by seven authors on fifty years of twin studies on over 17,000 traits conveyed an important take-away message: not even one trait was solely the result of either genetics or environmental experience. (Polderman et al. 2015) This relationship is complex; nurture is sometimes the dominant influence, but sometimes nature is. In reality, both provide significant influence on how people behave. (Sapolsky 2017)

Psychological tendencies to avoid physical violence, or improve one’s dominance status using physical violence, or an abiding concern for children and community are going to have complex environmental and genetic components—learned and inherited influences. Comparative, cross-cultural studies indicate, however, that whatever the learning environment, e.g. Quaker or ISIS, the genetic predisposition and observable adult behavior of the two sexes, certainly when considered as groups, are not identical for observed behavior involving use of physical violence, concern for children and a socially stable community, and a number of other significant behaviors as well. (Butovskaya et al. 2015, Schmitt et al. 2008, Schwartz & Rubel 2005)

Note that however influential genetics is to the behavioral choices of men and women—and it unquestionably is--individual behavior is highly adaptable and shaped by culture. (Sapolsk 2017) Individual behavior can change, people can learn to make new choices, and cultures can and do shift. Learning is what makes us so adaptable. This is a source of hope. What we see and experience now is not what inevitably must be.

Decision-making in Gender-balanced Groups

To illustrate how differences in male/female preferences play out when a gender-balanced group makes a socially critical decision, consider a simple example using war. Imagine a legislative body of twenty individuals, with equal numbers of men and women (koinoniarchy). They’ve been debating whether to go to war now—or—to let reflection and negotiation in Geneva play out longer. Emotions are running very high. In such a group, a not uncharacteristic vote of the men in a dominator society could be 7 in favor of declaring war—“we need to go kick ass”—and only 3 favoring more negotiation and reflection.

Clearly, not all men would favor war now. Some—maybe “cooler heads”—might opt for more careful reflection. If we compare that to a corresponding, hypothetical women’s vote in this culture, however, that would more likely be 2 of the women voting for war now, but 8 favoring extending reflection and negotiation a bit longer. It’s not that all the women would vote against charging into war, just that characteristically a greater percentage of them would favor more time for trying to find other options. In this not atypical gender-balanced group in a warring culture, the overall result is 9 votes for war now, but 11 for negotiating some more. This illustrates how giving women’s psychological preferences a voice in a gender-balanced group can effect a restraining or moderating influence on some characteristically male inclinations.

It’s critical to note, however, that this effect on more aggressive male inclinations won’t happen if only a token number of women are included. The exact percentage of women needed to influence a decision outcome in any social group undoubtedly differs by context and the question under consideration. For many situations the concepts of “critical mass” and “tipping point” have been offered to suggest a value around 30%, but the social chemistry of a group can sometimes be affected by even smaller female input. (Childs & Krook 2006, Dahlerup 1988)) The point being that, as history shows, the presence of only a few token women in any deciding body will not provide an effective counter to any male inclinations that differ from those of women.

Here is a real-life example of what happens when more women are included in leadership positions. In a paper looking at over 100 countries, the authors had noted that numerous previous behavioral studies found that women were more trust-worthy and public-spirited than men, are more likely to exhibit “helping” behavior, take stronger stances on ethical behavior, and behave more generously when faced with economic issues. This suggested to them that women would be less likely to sacrifice the common good for personal (material) gain. Looking deeper, they compared rates of government corruption to the percent representation of women in parliaments. It turned out that the greater the representation of women, they found the levels of corruption lower. (Dollar et al. 1999)

The Outcome of All-male Governing

In many decision-making contexts, the results achieved when women’s voices are included strongly suggests that having only one sex making all public choices all the time, e.g., all-male governing (patriarchy), might not always produce the very best result for communities over the long term (years, decades, hundreds of years, to say nothing of millennia).

Arguably that also includes the hypothetical condition of all-female governing (matriarchy). Due in part to women’s deep preference for social stability, often reflected in a tendency toward social conservatism, I speculated briefly that a society governed solely by women (we’ve never had one) would have its own pitfalls, one of the potential ones over long periods of time being a kind of social stagnation. (Hand 2003, p. 151)

As is true of so many things in life, both personal and social, the best results tend to emerge by finding balance. In the case of governing, I maintain that over time the balance of shared male/female governing is likely to produce the best results for our species. At least, would it not be worth a try?

Recorded history indicates that in the world’s dominant cultures, major social decisions involving governance have overwhelmingly been shaped by men for at least 2-3 thousands years. We know exactly how the world would work under patriarchies. We have done wonderful things. We’ve created technological masterpieces and works of stunning beauty, and explored insights into philosophy and religion. We’ve split atoms and discovered thousands of other worlds. We are indeed clever, surely a species worth saving, and for which we should build the best, most excellently nurturing future we can.

Also true, however, is that male psychological inclinations, manipulated by warmongers, have given us seemingly endless cycles of war and destruction. There is no reason to believe if we continue to operate under the same reality of male-dominated leadership that these repeated cycles of war and devastation would cease. Realistically, we may finally engage in a civilization-destroying one with weapons of mass destruction.

There is, however, strong reason for hope. Most men abhor war: actually killing other people. They can love playing at war as children, and war games as teens, even joining together to plan a war when they are adults. Men are good at and enjoy working in groups to achieve a goal, especially “winning.” (Wrangham & Benenson 2017) But normal men do not enjoy killing other people. They must be trained and conditioned to kill another human, the task of military indoctrination and conditioning. Actual participation in killing often has seriously damaging psychological effects. (Grossman 1995) That natural revulsion is a noteworthy, positive reality of what kind of animal we are.

Even what we call alpha males—a Dwight D. Eisenhower, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Nelson Mandela, Barack Hussein Obama—alpha males may find themselves involved in a war or even forced to take on an enemy that has attacked their community. But characteristically they don’t start wars.

Men who can be called hyper-alpha males, however, are different: the Genghis Khans, Napoleons, and Hitlers. Whatever good or bad they may leave in their wake, they are out of control men, virtually unconstrained by their culture, their women, or their own personal preferences. They’re emotionally driven to dominate all others, whether in a small tribal world or a world that spans continents, and are distinguished by being willing to kill or have others kill for them. They are the generators of war, the initiators of war, the warmongers.

They don’t wear a label that says “warmonger,” but they assemble an army and/or trigger theirs to strike the first blow. Contemporary versions of hyper-alpha men exist on all sides of our current conflicts. The many proximal reasons for why people make war—what they are fighting about (e.g., land, oil, religion)—have been discussed and written about in many books. I summarized the main reasons elsewhere. (Hand 2014, 31-34) In essence, war is the result of otherwise non-warring or even laudable male inclinations, described above, being malignantly manipulated by warmongering leaders in dominator cultures.

The percentage of hyper-alpha males in our populations is arguably very small. Perhaps ten percent, or even less. Warmongers are a tiny tail wagging the dog of civilization. To build that “better” future, the global community must at some point learn to identify contemporary warmongers and refuse to elevate them to positions of power, or when necessary, promptly remove them. They do harm by squandering resources needed to fully develop the cornerstones of a "better future." But even more urgently, they need to be removed before they light the fires to ignite a massive, global, and potentially existential Armageddon.

Butovskaya, M., V. Burkova, D. Karelin, & B. Fink. (2015) "Digit ration (2D:4D), aggression, and dominance in the Hadza

and the Datoga of Tanzania," American Journal of Human Biology, 27 (5), 620-627.

Childs, S. & M. L. Krook. (2006) "Should feminists give up on critical mass? A contingent yes." Politics & Gender.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X06251146. (accessed 25 November 2017.

Dahlerup, D. (1988) "From a small to a large minority: women in Scandinavian politics," Scandinavian Political Studies,

11 (4), 275-297.

Dollar, D., R. Fisman, & R. Gatti. (1999) "Are women really the “fairer” sex? Women and corruption in government."

Washington, DC: World Bank Development Research Group, Policy research report on gender and development

working paper series, no. 4.

Grossman, D. (1995) On Killing. The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, New York: Little Brown

and Company.

Hand, J. (2003) Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace, San Diego, CA, Questpath Publishing.

Hand, J. (2014) Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing.

Polderman, T. J. C, B. Benyamin, C.A. de Leeusw, P. F. Sullivan, A. van Bochoven, P. M. Visscher, & D. Posthuma. (2015)

"Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies," Nature Genetics, 47,

702-709.

Sapolsky, R. (2017) Behave. The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, New York, Penguin.

Schmitt, D. P., A. Realo, M. Voracek, & J. Allik. (2008) "Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big

Five personality traits across 55 cultures.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94 (1), 168-182.

Schwartz, S. H. & T. Rubel. (2005) Sex differences in value priorities: cross-cultural and multimethod studies, Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 1010-1028.

Wrangham, R. W. & J. F. Benenson. (2017) "Cooperative and competitive relationships within sexes." In Chimpanzees

and Human Evolution, (501-547), M. N. Muller, R. W. Wrangham, & D. Pilbeam (Eds.), Cambridge, MA, Harvard

University Press.

Zakaria, F. (1997) The rise of illiberal democracy. Foreign Affairs,

http://www.closer2oxford.ro/uploads/2012/06/12/The_Rise_of_Illiberal_Democracy.gf1ruw.pdf.

(accessed 12 March 2018).

and the Datoga of Tanzania," American Journal of Human Biology, 27 (5), 620-627.

Childs, S. & M. L. Krook. (2006) "Should feminists give up on critical mass? A contingent yes." Politics & Gender.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X06251146. (accessed 25 November 2017.

Dahlerup, D. (1988) "From a small to a large minority: women in Scandinavian politics," Scandinavian Political Studies,

11 (4), 275-297.

Dollar, D., R. Fisman, & R. Gatti. (1999) "Are women really the “fairer” sex? Women and corruption in government."

Washington, DC: World Bank Development Research Group, Policy research report on gender and development

working paper series, no. 4.

Grossman, D. (1995) On Killing. The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, New York: Little Brown

and Company.

Hand, J. (2003) Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace, San Diego, CA, Questpath Publishing.

Hand, J. (2014) Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing.

Polderman, T. J. C, B. Benyamin, C.A. de Leeusw, P. F. Sullivan, A. van Bochoven, P. M. Visscher, & D. Posthuma. (2015)

"Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies," Nature Genetics, 47,

702-709.

Sapolsky, R. (2017) Behave. The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, New York, Penguin.

Schmitt, D. P., A. Realo, M. Voracek, & J. Allik. (2008) "Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big

Five personality traits across 55 cultures.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94 (1), 168-182.

Schwartz, S. H. & T. Rubel. (2005) Sex differences in value priorities: cross-cultural and multimethod studies, Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 1010-1028.

Wrangham, R. W. & J. F. Benenson. (2017) "Cooperative and competitive relationships within sexes." In Chimpanzees

and Human Evolution, (501-547), M. N. Muller, R. W. Wrangham, & D. Pilbeam (Eds.), Cambridge, MA, Harvard

University Press.

Zakaria, F. (1997) The rise of illiberal democracy. Foreign Affairs,

http://www.closer2oxford.ro/uploads/2012/06/12/The_Rise_of_Illiberal_Democracy.gf1ruw.pdf.

(accessed 12 March 2018).

©2018 Judith Hand. All rights reserved. Login.

- Gateway Welcome

- Introduction

- About Me

- Major Interests

-

Publications

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War

-

War, Sex and Human Destiny

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 Background

- C2 Our Dilemma, Our Challenge War Defined

- C3 War - Nature or Nurture?

- C4 Sexual Dimorphism

- C5 Humans & Sexual Dimorphism

- C6 Equality for Women & Progress

- C7 Sex, Individuality, Leadership

- C8 Summary Conclusion

- C9 D. Fry - Life W/O War

- C10 AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C11 Global Peace System Accomplishments

- Acknowledgments

-

A Future Without War

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 - Introduction

- C 2 - The Single Most Important Idea

- C3 - How Far We've Already Come

- C 4 - Embrace The Goal

- C 5 - Empower Women

- C 6 - Enlist Young Men

- C7 - Ensure Essential Resources

- C8 - Foster Connectedness

- C9 - Promote Nonviolent Conflct Resolution

- C 10 - Provide Security & Order

- C 11 - Shift Our Economies

- C 12 - Spread Liberal Democracy

- C 13 - Differences Between Men & Woman About Aggression

- C14 - Women, Pivotal Catalyst for Positive Change

- C 15 - How Long It Would Take to Abolish War

- C 16 - Summary of AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C 17 - What Makes People Happy

- Acknowledgments

- Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace

- Fiction >

- Articles, Essays

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Contact