- Gateway Welcome

- Introduction

- About Me

- Major Interests

-

Publications

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War

-

War, Sex and Human Destiny

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 Background

- C2 Our Dilemma, Our Challenge War Defined

- C3 War - Nature or Nurture?

- C4 Sexual Dimorphism

- C5 Humans & Sexual Dimorphism

- C6 Equality for Women & Progress

- C7 Sex, Individuality, Leadership

- C8 Summary Conclusion

- C9 D. Fry - Life W/O War

- C10 AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C11 Global Peace System Accomplishments

- Acknowledgments

-

A Future Without War

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 - Introduction

- C 2 - The Single Most Important Idea

- C3 - How Far We've Already Come

- C 4 - Embrace The Goal

- C 5 - Empower Women

- C 6 - Enlist Young Men

- C7 - Ensure Essential Resources

- C8 - Foster Connectedness

- C9 - Promote Nonviolent Conflct Resolution

- C 10 - Provide Security & Order

- C 11 - Shift Our Economies

- C 12 - Spread Liberal Democracy

- C 13 - Differences Between Men & Woman About Aggression

- C14 - Women, Pivotal Catalyst for Positive Change

- C 15 - How Long It Would Take to Abolish War

- C 16 - Summary of AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C 17 - What Makes People Happy

- Acknowledgments

- Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace

- Fiction >

- Articles, Essays

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Contact

How I Came to Have My Academic Interests

The author in Jim Barton’s recording studio.

The author in Jim Barton’s recording studio.

Evolutionary Biology and Behaviour

By academic training I study how Earth’s organisms evolved by natural selection (and chance) over millennia to become what we observe today. I’m an evolutionary biologist.

As an undergraduate I took all the basic requirements for an anthropology major; I’ve always been fascinated by human behavior. But in my junior year the single anthropology professor left on sabbatical, so in my senior year I switched my major to the field in which I had already taken many classes—biology. I left for graduate school having taken all the basics: Evolutionary Theory, Ecology, Embryology, Genetics, and Anatomy.

By academic training I study how Earth’s organisms evolved by natural selection (and chance) over millennia to become what we observe today. I’m an evolutionary biologist.

As an undergraduate I took all the basic requirements for an anthropology major; I’ve always been fascinated by human behavior. But in my junior year the single anthropology professor left on sabbatical, so in my senior year I switched my major to the field in which I had already taken many classes—biology. I left for graduate school having taken all the basics: Evolutionary Theory, Ecology, Embryology, Genetics, and Anatomy.

Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology - UCLA

Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology - UCLA

It now seems like a very long time ago that I began graduate studies in biology in what was then called the zoology department at UCLA. I was a Masters student in “whole animal general physiology.” Those were the days before processes of specialization chopped biology fields into a plethora of compartments, so masters students in general physiology took required classes in many subjects: e.g., statistics (hated it), cell physiology, neurophysiology, genetics, and the anatomy and chemistry of basic body organs, from the cellular to the whole body level.

Max Planck Institute for Neuropsychiatry - Munich, Germany

Max Planck Institute for Neuropsychiatry - Munich, Germany

Thinking that I wanted to continue graduate studies and go for a Ph.D., I knew one requirement was that I must be reasonably fluent in two languages. I already had a so-so grasp of Spanish. I decided German would be my second choice. I saved up enough money to make it to Munich, Germany, and was fortunate enough to have learned skills in making implantable electrodes for and assisting in surgery for the study of brain function. Those skills got me a laboratory technician position at the Max Planck Institute for Neuropsychiatry where squirrel monkeys were the study subjects.

Paula and Rudy

Paula and Rudy

I did make electrodes and assisted in surgeries; most memorably I assisted Nobel Prize Winner Roger Sperry in a demonstration of his famous split-brain operation. Electrode stimulation sometimes evoked vocalizations by the monkeys, and no one had any idea what functions these vocalizations served. I was assigned to study the behavior and record the associated vocalizations of a small group of four, two males and two females, undisturbed in a small, glassed-in enclosure. I became intimately familiar with Napoleon, Oberon, Paula, and the youngest of the group, a young and frisky female named Quitta. During my time observing them, Paula gave birth to a baby male, Rudy. It was delightful to watch her interactions with him: protective and supporting. I knew then that my passion would not be to study brains, but to study whole animal behavior.

Hal and Judith Hand.

Hal and Judith Hand.

Some ten years later I returned to UCLA to earn a Ph.D. in Animal Behavior (a happy marriage and ten years of teaching high school biology had intervened). I specialized in communication, conflict resolution, and gender differences, focusing primarily on birds and primates…including that most amazing primate, Homo sapiens. My first study choice, chimpanzees, was ruled out. No chimpanzee research was being done in Los Angeles, and having recently married an LAPD police detective, I wasn’t free to move elsewhere. As explained below, my second choice, which would have been to study a marine mammal—dolphins—was also not going to be possible.

A wonderful year studying the behavior of a colony of gulls as a post-doctoral Smithsonian Fellow at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., came next. When the fellowship ended, I sought to find a tenure-track position in a university while working as a post-doctoral reaseach associate and instructor at UCLA. For several reasons, some described below, my search did not succeed. Very reluctantly I ended up leaving academia to write fiction. But even when I left the field of biology for many years, my interest in studies of both primate behavor and brain structure and function never wavered; I kept familiar with progress in both fields.

A wonderful year studying the behavior of a colony of gulls as a post-doctoral Smithsonian Fellow at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., came next. When the fellowship ended, I sought to find a tenure-track position in a university while working as a post-doctoral reaseach associate and instructor at UCLA. For several reasons, some described below, my search did not succeed. Very reluctantly I ended up leaving academia to write fiction. But even when I left the field of biology for many years, my interest in studies of both primate behavor and brain structure and function never wavered; I kept familiar with progress in both fields.

My Interest in Gender Differences

John Leon Latta

John Leon Latta

First, some background. I’m an Okie! I was born in Cherokee, Oklahoma when my father was away in the Navy, serving in the Pacific in WW II as a cook on a Navy vessel. He retuned when I was probably two years old and at first went into a grocery business with his older brother and their friend in Boulder Colorado. I loved him dearly. Sadly he died of cancer when I was nine, a malignant melanoma on his chest. My mother attributed the cancerous mole to too much sunbathing on board the deck of his ship. Later in Boulder he purchase a restaurant in the center of town, right across from the court house. I've been told he was a charismatic man. When he died at only thirty-two years of age, he had the biggest funeral the town had ever seen.

Wanda Hazel Latta

Wanda Hazel Latta

My mother was a lovely woman. She was a nurse. She had been raised as a stepdaughter, the youngest of four children, on a dirt-poor farm ten miles outside of Lacy, Oklahoma. She actually walked many dusty miles to get to school. She was on the girl’s basketball team in High School, and graduated valedictorian of her senior class.

She told me, I think when I was in High School, that she'd wanted to be a businesswoman, but that wasn’t possible because the only professions open to women then, even women from families having financial resources, were teaching and nursing. As I look back, this is quite sad…first because she didn’t love nursing, and second, all things considered, she would have been an enormously successful businesswoman. But at the time that she shared this truth of her reality with me, I simply accepted it as an interesting, if unfortunate, fact about her life. I felt no particular sadness and certainly no indignation.

She told me, I think when I was in High School, that she'd wanted to be a businesswoman, but that wasn’t possible because the only professions open to women then, even women from families having financial resources, were teaching and nursing. As I look back, this is quite sad…first because she didn’t love nursing, and second, all things considered, she would have been an enormously successful businesswoman. But at the time that she shared this truth of her reality with me, I simply accepted it as an interesting, if unfortunate, fact about her life. I felt no particular sadness and certainly no indignation.

This pattern of thought about what was suitable for women to do characterized and guided me for many years. For example, I remember clearly that in my sophomore year in High School we were offered some electives. I wanted to take “shop class,” where you could learn about how automobiles worked and how to repair them. But I was told that “shop” was only for boys. I, a girl, had to take “home economics”—instructions in cooking and sewing. In retrospect I wonder now why I wasn’t incensed. Clearly I am not a born rebel! I simply accepted that that was “the way things are.” I confess I did learn some very useful life skills about cooking and sewing, so all was not a total waste.

Thomas R. Howell

Thomas R. Howell

This pattern repeated sufficiently often for me to remember another such more serious incident. In 1979, as mentioned above, I applied to UCLA to enter the doctoral program in biology. My husband and I spent a lot of time boating so I was drawn to the idea of majoring in Marine Biology. But the first professor I went to in the Zoology Department, who would have been my logical sponsor, told me that it wouldn’t be possible for me to major in Marine Biology. Why? Because the department had only one teaching vessel, and it had only one “head” [bathroom]...and it was for men. Women could not use it.

Yes, he really said that. And more surprising as I look back is that I accepted this as a legitimate problem. I went away disappointed, but again not deeply angry or enraged. Another professor who studied dolphins couldn’t take on another student. And a third, a very famous professor in physiology, simply informed me that he didn’t take female graduate students. This did tick me off. I never forgot it. But at the time I also didn’t fight it.

I ended up studying the behavior of a sea bird species, Western Gulls, because, the only professor who would sponsor any interests of mine was Thomas R. Howell, a renowned ornithologist…a good man…a man who was willing to open the door for me, and to whom I owe my professional life. To him I remain deeply grateful.

Yes, he really said that. And more surprising as I look back is that I accepted this as a legitimate problem. I went away disappointed, but again not deeply angry or enraged. Another professor who studied dolphins couldn’t take on another student. And a third, a very famous professor in physiology, simply informed me that he didn’t take female graduate students. This did tick me off. I never forgot it. But at the time I also didn’t fight it.

I ended up studying the behavior of a sea bird species, Western Gulls, because, the only professor who would sponsor any interests of mine was Thomas R. Howell, a renowned ornithologist…a good man…a man who was willing to open the door for me, and to whom I owe my professional life. To him I remain deeply grateful.

Many similar experiences—being frustrated by being told “no”—had however produced the consequence that I was, by the age of twenty-two, a committed feminist. I considered myself the equal of many men I knew, and felt that women should be offered equal opportunities and rights. I was aware that a serious problem existed in society, and my views were staunchly along the line that, while there might be physical differences between men and women when it came to reproductive structures and reproductive behavior, men and women were otherwise behaviorally and intellectually similar….very diverse of course…but the sexes were equal….meaning to me, intellectually and emotionally the same.

My first enormous shock about the possibility that men and women might NOT be the same about behaviors or attitudes other than sexual ones came in graduate school. Here is how in Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace I described the event that set my feet firmly on the exploratory path of gender differences:

My Perspective on Gender Differences

In the intervening years since I was in graduate school massive amounts of research has focused on what is often called “gender differences" between men and women, boys and girls. It’s pretty safe to say at this point that in general, on many many tests of personality when things like educational and cultural factors are taken into consideration, and excluding sexual interests and behavior, there are comparatively few behavioral differences between the sexes. In addition, one thing we have learned for certain is that the range of possible human personality traits in both sexes is huge.

In War and Sex and Human Destiny, in the section on this website called “Sexual Dimorphism,” and in three books, Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace, Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War, and A Future Without War. The Strategy of a Warfare Transition, 2nd Ed. I explore questions of personality and motivation from the perspective of evolutionary biology. I have concluded that in at least five areas of social behavior and social preferences--1) social conflict, 2) the use of physical violence, 3) the practice of war, 4) concern for community and children’s welfare, and 5) preferences for social stability—powerfully substantial and consequential, genetically-based male/female differences do exist. All my non-fiction books explore the reproductive pressures that explain why men and women, during the course of our evolution, came to have these significant differences in social preference and behavior. And I have concluded that accepting “the way things are/were” when it comes to excluding women as participants in social affairs, forbidding them to follow their talents and interests, and especially excluding them as decision-makers in our lives, is not only not acceptable and certainly not fair, it is socially destructive.

The reality of human sexual dimorphism has shaped my perspective on human “gender differences.” Research, time, and social change continue. We in the United States are now, for example, deeply involved in debates about things that would have been unthinkable when I was in graduate school. Debates about whether there really are only two sexes, male and female. What about “transgender” individuals, and their rights in a democratic and free society? What about children who are born with the several physical characteristics that define the two sexes (most fundamentally the capacity for producing sperm or producing eggs) but who as they continue to develop or as adults feel the social and sexual preferences of the other sex? Should they undergo a sex-change operation?

Although I don't do so in the necessary detail that a full exploration of the subject of sexuality requires, in War and Sex and Human Destiny I briefly address this issue. This is necessary to avoid problems with sexual stereotyping and also to address questions about leadership. One way I look at this very complex issue is by saying that we, all of us, have a male side and a female side.

To illustrate what I mean, consider some other things about me. Let’s start with the fact that as a child I was definitely a girly-girl in many respects. My first remembered “toys” were two lovely little dolls, maybe ten inches tall, dressed fairy-tale like as the Snow Queen, all in white, and Sleeping Beauty. They were my dearest treasures. I loved their delicate beauty. I played jax, an alone game, and when my boy friends were playing marbles I tried it out, but soon lost interest. I identified strongly with fairy tales about princesses, and loved Rapunzel with her exquisitely long hair. But I never, ever, played dolls per se. In fact, I can only remember seeking out and playing with boys. And when we played Tarzan, I never would accept being the helper Jane….I always wanted to take the active role of Tarzan.

Although I don't do so in the necessary detail that a full exploration of the subject of sexuality requires, in War and Sex and Human Destiny I briefly address this issue. This is necessary to avoid problems with sexual stereotyping and also to address questions about leadership. One way I look at this very complex issue is by saying that we, all of us, have a male side and a female side.

To illustrate what I mean, consider some other things about me. Let’s start with the fact that as a child I was definitely a girly-girl in many respects. My first remembered “toys” were two lovely little dolls, maybe ten inches tall, dressed fairy-tale like as the Snow Queen, all in white, and Sleeping Beauty. They were my dearest treasures. I loved their delicate beauty. I played jax, an alone game, and when my boy friends were playing marbles I tried it out, but soon lost interest. I identified strongly with fairy tales about princesses, and loved Rapunzel with her exquisitely long hair. But I never, ever, played dolls per se. In fact, I can only remember seeking out and playing with boys. And when we played Tarzan, I never would accept being the helper Jane….I always wanted to take the active role of Tarzan.

Then, when I was about ten, I discovered Wonder Women. I was hooked. This was my role model. I began to collect every copy of the comic book. If they hadn't been stolen from my mother’s garage when I was in college I would be a rather wealthy woman today. One winter, when we still lived in Boulder Colorado, I made my three buddies help me build a pile of snowballs, and then I directed them throw them at me like they were bullets as I deflected them with the imaginary bracelets on my wrists.

One of the reasons I was told “no” so many times in my life, like the issue of auto mechanics versus home economics, was because I was always choosing to do or study things that were forbidden to girls or women. Had I wanted to marry and become a homemaker, the path of my life would have been much different, much easier. And in the end, I even picked a profession, science, which at the time was still a rare choice for a young women. In short, I consider myself to be a living embodiment of the concept that we all have both female and male sides…masculine and feminine aspects to our personalities.

Here, from War and Sex and Human Destiny, is how I address the issue of human individuality, based on the realaity that we all have a male side and a female side, and how that relates to issues of leadership:

One of the reasons I was told “no” so many times in my life, like the issue of auto mechanics versus home economics, was because I was always choosing to do or study things that were forbidden to girls or women. Had I wanted to marry and become a homemaker, the path of my life would have been much different, much easier. And in the end, I even picked a profession, science, which at the time was still a rare choice for a young women. In short, I consider myself to be a living embodiment of the concept that we all have both female and male sides…masculine and feminine aspects to our personalities.

Here, from War and Sex and Human Destiny, is how I address the issue of human individuality, based on the realaity that we all have a male side and a female side, and how that relates to issues of leadership:

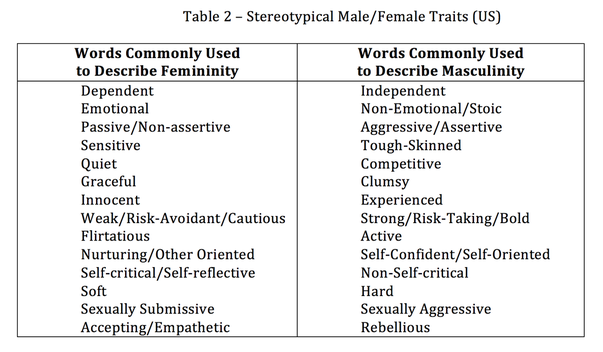

Sex and Individuality

“At this point, individual human behavior requires attention because of the danger of sexual stereotyping, and because we need to consider what kind of visionary leadership is essential to shape a positive human destiny. Sexual behavioral dimorphism that affects group behavior is a reality for some personality traits. It’s the reason why so many cultures recognize a yin and yang, a sun and moon, a “vive la difference.” Individual human beings, however, should be judged and treated individually. Except for identical twins, no two humans inherit identical DNA, nor are they reared in identical environments or experience the same social interactions. Thus the wonderful reality for individuals is psychological uniqueness.

“The table, randomly selected from an Internet Google search, lists personality traits in the United States commonly thought of by many as female and male. In actuality, every person is a complex combination of what their society considers to be male and female traits. In everyday terms, in differing degrees we all have a female side and a male side.

“But consider that some of us are way more in touch with our female side: say a person—boy or girl, man or woman—who is very emotional, non-assertive, sensitive, a bit too self-critical, and also sweetly nurturing and empathetic. And some of us are way more in touch with our male side: someone—boy or girl, man or woman—who is aggressive, competitive, very self confident/self-oriented, non-self-critical, in fact rebellious and risk-taking. And some of us display a mixture of traits that can be described as being in touch more equally with both male and female sides. A man who is not only aggressive, self-confident, competitive, and bold, but also self-reflective and empathetic. A woman who is not only nurturing and empathetic, but also independent, competitive, and bold. Human embryonic development is so complex that someone can be born having physical sex characteristics of one sex but feeling the biological preferences and urges characteristic of the other sex. Essentially, all societies have available to them, if they choose to take advantage of it, a rich variety of individuals. This is a massive, arguably splendid, diversity that can either be embraced or molded into rigid stereotypes.

“But consider that some of us are way more in touch with our female side: say a person—boy or girl, man or woman—who is very emotional, non-assertive, sensitive, a bit too self-critical, and also sweetly nurturing and empathetic. And some of us are way more in touch with our male side: someone—boy or girl, man or woman—who is aggressive, competitive, very self confident/self-oriented, non-self-critical, in fact rebellious and risk-taking. And some of us display a mixture of traits that can be described as being in touch more equally with both male and female sides. A man who is not only aggressive, self-confident, competitive, and bold, but also self-reflective and empathetic. A woman who is not only nurturing and empathetic, but also independent, competitive, and bold. Human embryonic development is so complex that someone can be born having physical sex characteristics of one sex but feeling the biological preferences and urges characteristic of the other sex. Essentially, all societies have available to them, if they choose to take advantage of it, a rich variety of individuals. This is a massive, arguably splendid, diversity that can either be embraced or molded into rigid stereotypes.

Sex and Leadership

“So to start a social revolution headed toward a positive “better” destiny, what kind of leaders should we follow? Who should we elect to lead the change? Obviously, a leader cannot be shy. He or she must be in touch with aspects thought to characterize their male side like being assertive, independent, and bold. But wisdom demands that she or he is also able to be self-critical and reflective, able to change their mind when needed; stubbornly holding to an unworkable, unfavorable positon is fatal to good leadership. And to lead well, rather than be a bully or tyrant, he or she needs to be in touch with traits thought to characterize a female side, like being accepting and empathetic with regard to the people they lead.

“Our very worst choice for leaders would be anyone, man or woman, having traits guaranteed to foster continuation of the world’s dominator, warring, patriarchal cultures. Someone aggressive, competitive, non-self-critical, strongly self-oriented and woefully lacking in being accepting or empathetic. They should not be elevated to leadership. They should not be tolerated as leaders. Not if we want to “try something different” that might bring about a lasting, less destructive and vastly more nurturing future.”

“Our very worst choice for leaders would be anyone, man or woman, having traits guaranteed to foster continuation of the world’s dominator, warring, patriarchal cultures. Someone aggressive, competitive, non-self-critical, strongly self-oriented and woefully lacking in being accepting or empathetic. They should not be elevated to leadership. They should not be tolerated as leaders. Not if we want to “try something different” that might bring about a lasting, less destructive and vastly more nurturing future.”

My Interest in War

Eugene Morton

Eugene Morton

I wasn’t interested in and certainly not much concerned about war until I was fifty-nine years old (no father, brothers, or friends of an age to be subject to the draft). After securing my Ph.D. I was awarded a one-year post-doctoral Smithsonian Fellowship at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.. I was sponsored by ornithologist Gene Morton. Here was another man who was a gatekeeper who let me in, and to whom I am deeply indebted. This turned out to be one of the most enjoyable and productive years of my life. What I studied about social conflict resolution would later be critical to my thinking about war...and about how to resolve conflicts without war.

Laughing Gull Pair

Laughing Gull Pair

In a very large flight cage, the zoo had a captive group of 24 gulls, Laughing Gulls and Silver Gulls. The birds had plenty of room to set up territories and breed. Because I wanted to study their vocal and other behavior individually, the birds were trapped, identifying bands were placed on their legs, they were sexed using a laparoscope, and then they were released back into the cage.

One of the things I studied was conflict-resolving behavior of mated pairs. Keep in mind that male gulls are always larger in size than their mates and so, in theory, would easily be able to dominate their mate. I looked at how mated gulls dealt with food and nesting issues. To my surprise, the larger male did not dominate his smaller mate. Rather they used “egalitarian” behaviors…either “sharing” a big piece of a desirable food object side-by-side, or using a “first come first served rule” when I threw out tasty tiny tidbits. Most astonishing to me was that to decide which bird would incubate their eggs at any time they used quite a number of different physical and vocal signals to determine which one wanted most strongly to incubate or to quit incubating....they "negotiated." I wrote two papers explaining this novel finding of egalitarian conflict resolving behavior in an animal species. There clearly are others ways to resolve differences besides “win-loose.”

One of the things I studied was conflict-resolving behavior of mated pairs. Keep in mind that male gulls are always larger in size than their mates and so, in theory, would easily be able to dominate their mate. I looked at how mated gulls dealt with food and nesting issues. To my surprise, the larger male did not dominate his smaller mate. Rather they used “egalitarian” behaviors…either “sharing” a big piece of a desirable food object side-by-side, or using a “first come first served rule” when I threw out tasty tiny tidbits. Most astonishing to me was that to decide which bird would incubate their eggs at any time they used quite a number of different physical and vocal signals to determine which one wanted most strongly to incubate or to quit incubating....they "negotiated." I wrote two papers explaining this novel finding of egalitarian conflict resolving behavior in an animal species. There clearly are others ways to resolve differences besides “win-loose.”

When the fellowship at the zoo ended, I returned home to Los Angeles, and while teaching and writing as a research associate at UCLA, I sought to secure a tenure-track university professorship or a suitable position in some other research setting where I could also mentor students. For several reasons the search failed. I was told that my age was one barrier….hiring committees were looking for younger candidates who would teach and work longer before retiring and I was forty-seven years old. Also, my husband was still working as an LAPD detective and could not retire for a number of years, so my search for a university position was somewhat restricted geographically.

And then there were two cases where young men were hired for positions I also applied for, and for which I felt I was better qualified. Much better qualified! This did not sit well. And finally, two female colleagues were hired at good institutions, one of them married to a man who was already a faculty member there, and the other who was the mistress of an established faculty member. After much agony and soul searching about the likelihood of achieving my dream of a lifetime of research as a tenured professor, I made a major life-altering decision, and switched to my second career choice, writing fiction.

And then there were two cases where young men were hired for positions I also applied for, and for which I felt I was better qualified. Much better qualified! This did not sit well. And finally, two female colleagues were hired at good institutions, one of them married to a man who was already a faculty member there, and the other who was the mistress of an established faculty member. After much agony and soul searching about the likelihood of achieving my dream of a lifetime of research as a tenured professor, I made a major life-altering decision, and switched to my second career choice, writing fiction.

I would not return to academic considerations about social conflicts, including war, for over ten years. I published several novels, always featuring a strong woman as the central character, partnered with a strong man. Male/female partnership was a theme of these novels and also ended up being a central theme in my conclusions about ending war and building a more peaceful and nurturing human future.

In one of these stories, Voice of the Goddess, I used my background in both biology and anthropology to portray a nonviolent, women-centered and goddess-worshipping island culture inspired by the Minoan culture of Bronze Age Crete. My heroine was their High Priestess. Her romantic interest was a warrior from a mainland, patriarchal, warring culture, inspired by what we know about the Mycenaeans.

To promote the story I gave a talk entitled “If women ran the world, how might things be different?” Because of natural selection for reproductive success, I pointed out, our two sexes, as groups, do not have the same psychological priorities and responses when it comes to resolving conflicts, including conflicts that lead to wars. If women did, indeed, run the world, there would be no war. If our dominant societies were matriarchies (all-female governing) rather than patriarchies (all-male governing) the world would reflect female preferences for conflict resolution…and those preferences are for women in general strongly predisposed to avoid physical violence of all kinds, including war.

A friend who is a gifted book editor said if I would turn the talk into something book length she would drop everything to edit it….because she had never heard anything like what I was saying. I was making the case, from biology, that if we wanted it badly enough to make appropriate social changes, we could eliminate war. In fact, influenced by Konrad Lorenz’s book On Aggression, she had quite the opposite belief that war was a part of human nature. She thought that I had a strong case for a profoundly important cause.

In one of these stories, Voice of the Goddess, I used my background in both biology and anthropology to portray a nonviolent, women-centered and goddess-worshipping island culture inspired by the Minoan culture of Bronze Age Crete. My heroine was their High Priestess. Her romantic interest was a warrior from a mainland, patriarchal, warring culture, inspired by what we know about the Mycenaeans.

To promote the story I gave a talk entitled “If women ran the world, how might things be different?” Because of natural selection for reproductive success, I pointed out, our two sexes, as groups, do not have the same psychological priorities and responses when it comes to resolving conflicts, including conflicts that lead to wars. If women did, indeed, run the world, there would be no war. If our dominant societies were matriarchies (all-female governing) rather than patriarchies (all-male governing) the world would reflect female preferences for conflict resolution…and those preferences are for women in general strongly predisposed to avoid physical violence of all kinds, including war.

A friend who is a gifted book editor said if I would turn the talk into something book length she would drop everything to edit it….because she had never heard anything like what I was saying. I was making the case, from biology, that if we wanted it badly enough to make appropriate social changes, we could eliminate war. In fact, influenced by Konrad Lorenz’s book On Aggression, she had quite the opposite belief that war was a part of human nature. She thought that I had a strong case for a profoundly important cause.

Again a life-path crossroads was offered. I could continue writing fiction, a career that was taking off nicely. Or write a piece of nonfiction about human social conflicts, gender differences, the potential for social progress, and for ending war. After several days of soul-searching, a strongly felt obligation to honor all those many years of training and research won out. The result was my first book on this subject, Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. Other books followed: A Future Without War, and Shift: The Beginning of War, the Ending of War. So it is that by a circuitous route, my most recent books, War and Sex and Human Destiny and A Future Without War are also an offspring of a talk to promote a novel.

At the time I made the choice I strongly suspected that if I stepped onto the nonfiction train I might never get back onto the fiction one. And that’s what did happen. I only wrote one more novel. But if you live long enough….at the time of this writing I have begun research for a new novel, set years into the future, in fact a six part series of them. This time women, and their role in shaping the future, will be the theme.

At the time I made the choice I strongly suspected that if I stepped onto the nonfiction train I might never get back onto the fiction one. And that’s what did happen. I only wrote one more novel. But if you live long enough….at the time of this writing I have begun research for a new novel, set years into the future, in fact a six part series of them. This time women, and their role in shaping the future, will be the theme.

My Interest in a Global Peace System

On this website, under the nav bar for “Major Interests,” is a page dedicated to the subject War. It moves in more or less chronological progression through my journey of discovery on this subject: what I learned, how I learned it, and what I believe about the actual human potential to abolish war. I now see using physical violence by groups of humans slaughtering other groups of humans while destroying their home and communities as a means to resolve our many kinds of conflicts as a form of cultural insanity. It's an insanity within which we are currently entrapped. Moreover, I consider that war is a cultural product of all-male governing (our many varieties of patriarchies).

Eventually I concluded

1) that ending war is within human capability because it is not an innate aspect of human nature, and

2) war is so deeply enmeshed in the world’s dominant cultures that ending it would require so many big changes that the project could be likened to putting a permanent colony on the Moon or Mars; a major challenge, but not impossible given our truly astounding capacity to learn and to change our behavior.

Not surprisingly, people inevitably ask me, How? How do we move from where we are to where you are saying we could go?

1) that ending war is within human capability because it is not an innate aspect of human nature, and

2) war is so deeply enmeshed in the world’s dominant cultures that ending it would require so many big changes that the project could be likened to putting a permanent colony on the Moon or Mars; a major challenge, but not impossible given our truly astounding capacity to learn and to change our behavior.

Not surprisingly, people inevitably ask me, How? How do we move from where we are to where you are saying we could go?

For several years I wrestled with that “how” question. It really should be obvious now to everyone, given our lengthy historical record chronicling war after war, that making a war to bring peace only inevitably leads to more wars. Apparently, and sadly, it is not obvious, because politicians keep telling us we need one more war so we can have peace. WW I, the “war to end all wars,” should have been a totally final nail in the coffin of that notion.

So if yet another war to end all wars won’t work, then how? I began a deep dive into study of major successful social change movements using nonviolent means. How did Gandhi work? And the American suffragists who won the right of women to vote? And the American civil rights movement, spearheaded by Martin Luther King, Jr.?

So if yet another war to end all wars won’t work, then how? I began a deep dive into study of major successful social change movements using nonviolent means. How did Gandhi work? And the American suffragists who won the right of women to vote? And the American civil rights movement, spearheaded by Martin Luther King, Jr.?

I learned about Mohandas Gandhi’s distinction between Obstructive Program and Constructive Program. Essentially this master social change agent recognized that to make a change that can last--not just any temporary change but one that can last--requires that people learn new ways of behaving….so providing education and training and fostering real-world change in behavior is a necessary component of a social change movement with enduring outcome. Berkeley Professor Michael Nagler, in his small but very educational pamphlet Hope or Terror? Gandhi and the Other 9/11, called these types of actions Gandhi’s Constructive Program. They are the “good works” aspect of a nonviolent social change campaign. For Gandhi’s movement it involved, for example, teaching Indians to weave their own cloth, efforts to tackle the worst aspects of the caste system, and working to improving the lot of women.

But Gandhi knew that “good works” alone would not be effective in changing a deeply embedded social construct. Direct action would be required. It’s necessary to confront the old system head on. And the path to success was to mobilize citizens to use nonviolent direct action: marches, work stoppages, sit-ins, boycotts, and so on. This Gandhi called Obstructive Program.

So, how would these two types of ingredients of an action plan for social change—good works and nonviolent direct action—be applied to ending war? The essence of such an action plan, describing both Constructive and Obstructive Programs, can be found in the essay, “To Abolish War.” Another short essay, “Dismantling the War Machine” suggests possible Obstructive Program targets activist citizens can apply against the modern war machine: demand elimination of land mines, cluster bombs, nuclear weapons; prevent deployment of offensive weapons in space or autonomous robots and drones; use of tools of nonviolent direct action (boycott, divestment, strikes, marches) to force leaders to adopt a peace treaty (e.g., in Palestine, in Syria, in Yemen).

So, how would these two types of ingredients of an action plan for social change—good works and nonviolent direct action—be applied to ending war? The essence of such an action plan, describing both Constructive and Obstructive Programs, can be found in the essay, “To Abolish War.” Another short essay, “Dismantling the War Machine” suggests possible Obstructive Program targets activist citizens can apply against the modern war machine: demand elimination of land mines, cluster bombs, nuclear weapons; prevent deployment of offensive weapons in space or autonomous robots and drones; use of tools of nonviolent direct action (boycott, divestment, strikes, marches) to force leaders to adopt a peace treaty (e.g., in Palestine, in Syria, in Yemen).

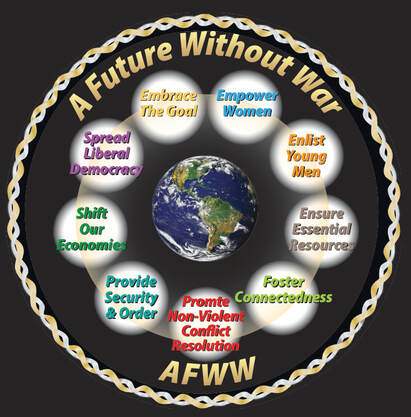

LOGO - A Future Without War

LOGO - A Future Without War

The Constructive Program “good works” elements that would have to be undertaken to create a sustainable global peace can be grouped by subject or interest areas, many of which overlap or are significantly intertwined. To facilitate visualization of and bring some coherance to these many elements, I used nine categories, or “cornerstones.” They are the subjects and focus of the website www.AFutureWithoutWar.org which explains each in detail. The section “War” on this personal website briefly explains them. The www.afww.org website provides lists, with contact information, for hundreds of organizations and projects around the globe already advancing these “good works.”

What became obvious to me, however, is that in spite of thousands of efforts to do these necessary things required to abolish war, war is still with us. All of these good works haven't ended war....and don't appear close to doing so. Why?

Comparing all successful social change movements that have withstood the testing of time reveals a critical shared characteristic: FOCUS. In each case there was a very specific goal behind which a great many people were mobilized. Successful (i.e. lasting) movements that have succeeded in forcing major social paradigm shifts do NOT try to solve multiple possible problems: the world simply has too many of them. Successful movements, especially those that get results that endure, have had a core of knowledgeable leaders who understand how to use nonviolent direct action (i.e., Obstructive Program), and this core leadership develops a plan of action and steers the movement through its many difficulties, keeping it focused on the ultimate goal.

Moreover, this goal, Gandhi made clear, cannot be vague. A desirable but nevertheless too vague to visualize goal can’t keep many people focused and united over the time it takes to bring about a major social shift. The stated and shared end-goal must involve something very discrete, a visible end-point toward which all "good works" actions are directed. For example, “to end war” is way too vague. How do you plan the steps to get there so that it is clear to all participants how each step functions in the greater cause? To keep workers in the field motivated, a social change movement’s participants must be able to see, even if only vaguely at the moment, how each bit of progress they’ve made has contributed to reaching the very clearly defined, recognizable shared and achievable end-goal. For example:

The writings of Harvard Professor Gene Sharp, such as his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle. 20th Century Practice and 221st Century Potential, and papers like “Why civil resistance works: the strategic logic of nonviolent conflict” by Maria Stephen and Erica Chenoweth, and many other books and papers by people who have studied the extraordinary power of nonviolent social change convinced me that any plan to end war needed to be built on the basic strategies of nonviolent struggle.

Moreover, this goal, Gandhi made clear, cannot be vague. A desirable but nevertheless too vague to visualize goal can’t keep many people focused and united over the time it takes to bring about a major social shift. The stated and shared end-goal must involve something very discrete, a visible end-point toward which all "good works" actions are directed. For example, “to end war” is way too vague. How do you plan the steps to get there so that it is clear to all participants how each step functions in the greater cause? To keep workers in the field motivated, a social change movement’s participants must be able to see, even if only vaguely at the moment, how each bit of progress they’ve made has contributed to reaching the very clearly defined, recognizable shared and achievable end-goal. For example:

- Gandhi – the British must leave India – India must have independence.

- American Suffragists – there must be a constitutional amendment giving voting rights to women.

- US Civil Rights Movement – an end to segregation in public places and a ban on employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

- Women’s Action for a Liberian Peace – secure a treaty to end the Liberian civil war.

The writings of Harvard Professor Gene Sharp, such as his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle. 20th Century Practice and 221st Century Potential, and papers like “Why civil resistance works: the strategic logic of nonviolent conflict” by Maria Stephen and Erica Chenoweth, and many other books and papers by people who have studied the extraordinary power of nonviolent social change convinced me that any plan to end war needed to be built on the basic strategies of nonviolent struggle.

Success for Any Massive Project Requires Coordination

Success for Any Massive Project Requires Coordination

What now seems obvious is that an end to war won’t happen by lucky chance nor by some gradual, blind process of positive historical change. That one way or the other, a campaign to end war will be so challenging that the thousands of cornerstone undertakings must have some form of central coordination. There must be a shared vision. And that vision must be supplied by ending-war campaign leadership.

Any massive project, from building the pyramids to putting a man on the Moon, requires coordination. Without coordination the cornerstone elements are all doing “their own thing,” and the massive people power needed to force a major paradigm shift to a warless future is too dispersed. That is the global community’s present condition.

Knowledgeable and visionary leaders must emerge and work together to unite and focus Constructive and Obstructive Programs. In unity there will be sufficient power to actually take the war machine apart.

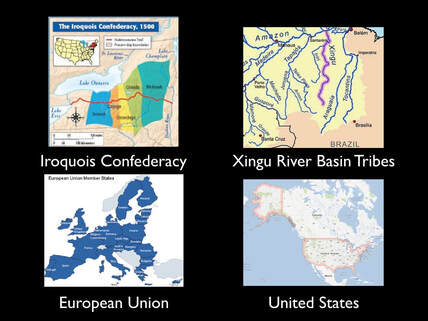

So the question was, what could be the vision behind which all Constructive and Obstructive projects could unite? What could be that concrete, uniting goal? In 2012, the anthropologist Douglas Fry published an article in the journal Science entitled “Life Without War."] In it he described the six characteristics of “peace systems.” [if you use this link, scroll down a page to find the article's beginning]

Here I had found the concrete uniting goal I’d spent years seeking for: the establishment of a global peace system, enforced by a very concrete working and enforceable global peace treaty.

In Fry’s paper he describes a number of actual peace systems. He looked in detail at three very different cultures: the Iroquois Nation in North America, three tribes living in a river basin in Brazil, and the European Union. Actually, the United States is also a peace system that shares the same six characteristics. In this way, Fry makes clear that the idea of a peace system is not utopian: they have existed and do exist if people have the will to form and maintain them. In addition to his paper in Science, the essay “The Shared Characteristics of Peace Systems” describes these six defining shared characteristics.

As of this date (September 2019) I do not yet see the emergence of a core leadership behind any specific end-goal, such as the establishment of a global peace system. A number of separate peace-oriented groups have embraced an effort to unite so as to advance each of their diverse projects. I worked at its inception with a group we named World Beyond War.org. It does have as its goal to connect the hundreds if not thousands of peace organizations and peace activists globally behind the shared desire to end wars. A very well organized movement is called Activate: The Global Citizen Movement, does have a specific end goal: to advance projects that will end extremely poverty (this includes, for example, empowering women). But that goal is very diffuse, hard to measure, and does not include ending war.

These efforts do not yet have a shared, singular, discrete and observable end-goal as readily measurable as the establishment of a global peace system to which all members, no matter what their other interests may be, nevertheless devote some time and resources. Particularly important from my view will be to unite all cornerstone elements in shared Obstructive Programs that confronts the current, warring world system directly with the challenge to convene and make an enforceable Global Peace Treaty [I stress enforceable because this lack is currently the Achilles heel of the United Nations, whose founding objective was, in fact, to end wars].

Here I had found the concrete uniting goal I’d spent years seeking for: the establishment of a global peace system, enforced by a very concrete working and enforceable global peace treaty.

In Fry’s paper he describes a number of actual peace systems. He looked in detail at three very different cultures: the Iroquois Nation in North America, three tribes living in a river basin in Brazil, and the European Union. Actually, the United States is also a peace system that shares the same six characteristics. In this way, Fry makes clear that the idea of a peace system is not utopian: they have existed and do exist if people have the will to form and maintain them. In addition to his paper in Science, the essay “The Shared Characteristics of Peace Systems” describes these six defining shared characteristics.

As of this date (September 2019) I do not yet see the emergence of a core leadership behind any specific end-goal, such as the establishment of a global peace system. A number of separate peace-oriented groups have embraced an effort to unite so as to advance each of their diverse projects. I worked at its inception with a group we named World Beyond War.org. It does have as its goal to connect the hundreds if not thousands of peace organizations and peace activists globally behind the shared desire to end wars. A very well organized movement is called Activate: The Global Citizen Movement, does have a specific end goal: to advance projects that will end extremely poverty (this includes, for example, empowering women). But that goal is very diffuse, hard to measure, and does not include ending war.

These efforts do not yet have a shared, singular, discrete and observable end-goal as readily measurable as the establishment of a global peace system to which all members, no matter what their other interests may be, nevertheless devote some time and resources. Particularly important from my view will be to unite all cornerstone elements in shared Obstructive Programs that confronts the current, warring world system directly with the challenge to convene and make an enforceable Global Peace Treaty [I stress enforceable because this lack is currently the Achilles heel of the United Nations, whose founding objective was, in fact, to end wars].

After experiencing the massive destruction of WW II, visionary leaders in Europe resolved to build a kind of United States of Europe with the specific goal to end the destructive wars that had repeatedly afflicted their peoples. The EU was assembled in a relatively short time, a couple of decades, under this vision, and it has kept the peace for over 70 year. I would like to live to see the people of planet Earth come together to create a Global Peace System.

“The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood,

the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.

We are made of starstuff.”

Carl Sagan, Cosmos

the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.

We are made of starstuff.”

Carl Sagan, Cosmos

Astronomy image credit: NASA

©2018 Judith Hand. All rights reserved. Login.

- Gateway Welcome

- Introduction

- About Me

- Major Interests

-

Publications

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Shift: The Beginning of War, The Ending of War

-

War, Sex and Human Destiny

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 Background

- C2 Our Dilemma, Our Challenge War Defined

- C3 War - Nature or Nurture?

- C4 Sexual Dimorphism

- C5 Humans & Sexual Dimorphism

- C6 Equality for Women & Progress

- C7 Sex, Individuality, Leadership

- C8 Summary Conclusion

- C9 D. Fry - Life W/O War

- C10 AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C11 Global Peace System Accomplishments

- Acknowledgments

-

A Future Without War

>

- Table of Contents

- C1 - Introduction

- C 2 - The Single Most Important Idea

- C3 - How Far We've Already Come

- C 4 - Embrace The Goal

- C 5 - Empower Women

- C 6 - Enlist Young Men

- C7 - Ensure Essential Resources

- C8 - Foster Connectedness

- C9 - Promote Nonviolent Conflct Resolution

- C 10 - Provide Security & Order

- C 11 - Shift Our Economies

- C 12 - Spread Liberal Democracy

- C 13 - Differences Between Men & Woman About Aggression

- C14 - Women, Pivotal Catalyst for Positive Change

- C 15 - How Long It Would Take to Abolish War

- C 16 - Summary of AFWW 9 Cornerstones

- C 17 - What Makes People Happy

- Acknowledgments

- Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace

- Fiction >

- Articles, Essays

-

Non-Fiction

>

- Contact